Alfred was born in Prior’s Lee, Salop in Shropshire in about 1910, to Alfred & Annie Leyland. He had an older brother & sister, Arthur and Winifred as well as one sister, Audrey, who was less than a year younger than him.

Most of the following information has been gathered from newspaper cuttings preserved in scrap books by the Middlesbrough Fire Brigade of the time.

We know nothing about Alfred’s early life, but in 1931, when he was 21 years old, he joined Manchester Fire Brigade. Seven years later he was Deputy Chief in Stockton-on-Tees Fire and Ambulance Brigade.

He appears to have been quite ambitious as in 1941, only 10 years after he began his career in the Fire service, he became Officer in Charge of the Western Division in Newcastle and a year later, 1942, was responsible for the whole of the Newcastle area.

In 1945 he moved to Middlesbrough, where he would remain for the next 18years. At this time his post was Sub-District Commander.

Three years later in 1948 he became Middlesbrough’s Chief Fire Officer a post he would keep for approximately 16 years.

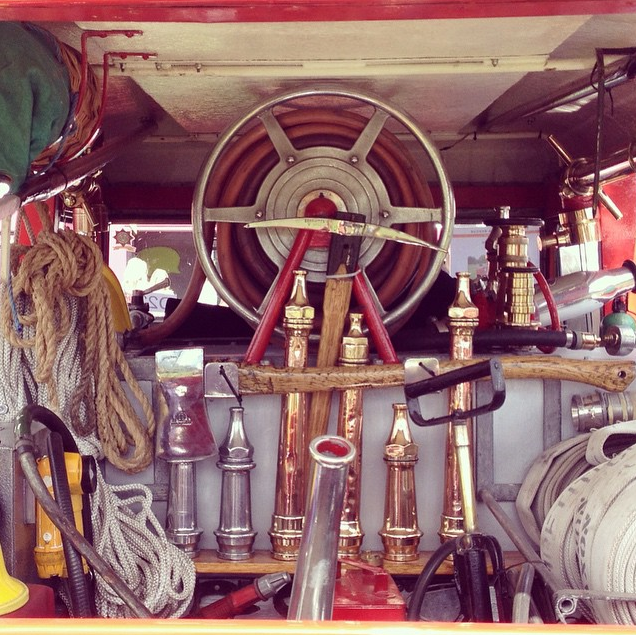

On July 12th 1951 Middlesbrough Fire Brigade officially opened an extension to their Workshops building.

In November 1955 Alfred was presented with the Queens Medal for long service and good conduct. A picture and article, shown here, were in the Evening Gazette of the time.

A month long Exhibition, to mark the centenary of Middlesbrough Fire Service was opened 2nd September 1955. Alfred was very much hands on with every part of this successful exhibition and even organised a huge painting of Middlesbrough, displaying futuristic imaginary of skyscrapers with fire fighting techniques showing rescues using helicopters and wide television screens.

Only a year later, 14th February 1956, the queen mother presented Alfred with an OBE. Here is a lovely photograph taken the next day, of Alfred showing his O.B.E. to his proud wife and two daughters, in the Northern Echo.

I did find an interesting little snippet in an article written in January 1956 which told of how the Chief Fire Officer had been complaining of his house, 113 Park Road South, being extremely cold and impossible to heat and as a result was affecting both his family’s health as well as his own. He requested the Fire Brigade Committee look into this and asked them to include a further £250 in the 1955/56 estimates to heat the house.

In October 1959, Leyland was appointed President of the Chief Fire Officers Association – a position he took very seriously, remarking that his post required he ‘demonstrate in a manner beyond reproach the sense of responsibility, loyalty enabling a Chief Officer to serve his council and community.’

In 1963, a year before Alfred should have retired and at the age of 54, he accepted a post to join a 12 man team within the Fire Department of the Home Office in London as Assistant Inspector. His resignation was accepted and he handed over his post to the new Chief Fire Officer, Mr Harry Johnson, leaving at the end of July to begin his new position.

Alfred died aged 69 in Cheltenham, Gloucestershire in December 1978, after a long and successful career working in fire prevention.