John Shiels was born in Girvan, Scotland in 1841 to Patrick and Margaret Shiels who had emigrated from Ireland. Patrick worked as a traveller, hawking of soft goods, and in 1851 he and John (who was only 10) were lodging with other Irish hawkers in Glasgow.

We have no further information about John until 1860, when at the age of 20 he was appointed a Police Constable in Leeds City Police. Records show that John’s previous employment was as a commercial ‘traveller’ like his father, and that he was recommended for the position by a ‘Major General Johnson of Garnsallow’. (We have not been able to establish where Garnsallow is, or how John came to meet Major General Johnson; one theory suggests that as a teenager John may have joined the armed forces and fought alongside Johnson during the Indian Mutiny of 1857).

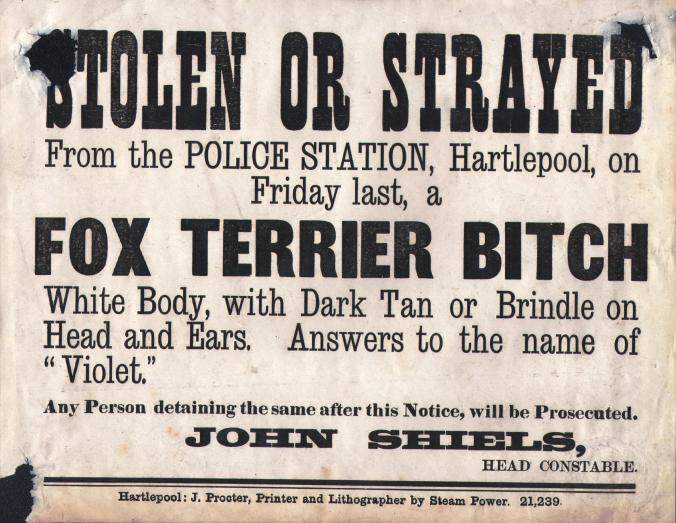

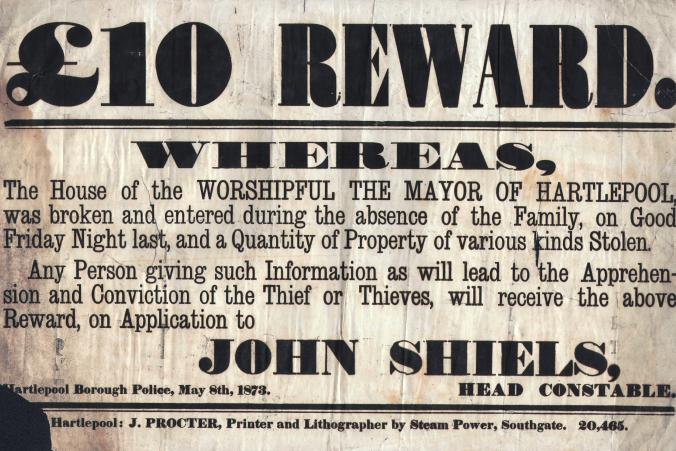

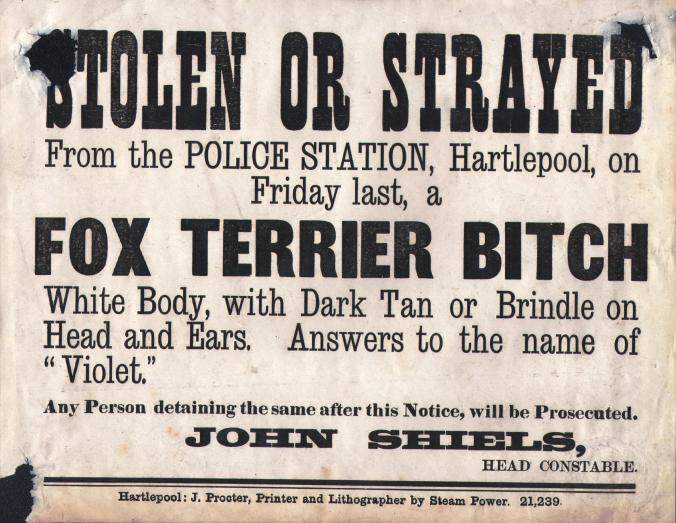

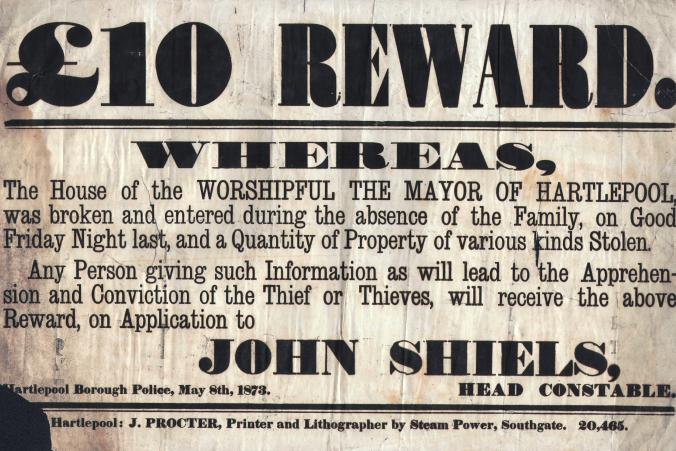

Police notice from Head Constable of the Hartlepool Borough Police, John Shiels, circa 1870-1875.

John was described in the Leeds City Police appointment book as having “blue eyes, light brown hair, fair complexion with a height of 5’ 9¾”. In August 1861 he was promoted to 2nd class Constable and was subsequently promoted to 1st class in June 1862. A year later he was reprimanded for disobedience of orders. That same year he married Selina Goodliff and their first child Margaret was born in 1864.

In June 1865 John was reprimanded again, this time for ‘improper conduct’. However, he must have been thought of highly at Leeds as later that month he was also promoted to Sergeant with a weekly wage of 23 shillings. A year later John was promoted again to 2nd class Sergeant and his pay increased to 24 shillings and 6 pence a week. I’m sure a much needed pay increase to support his growing family was welcomed as his second child Patrick was born that year.

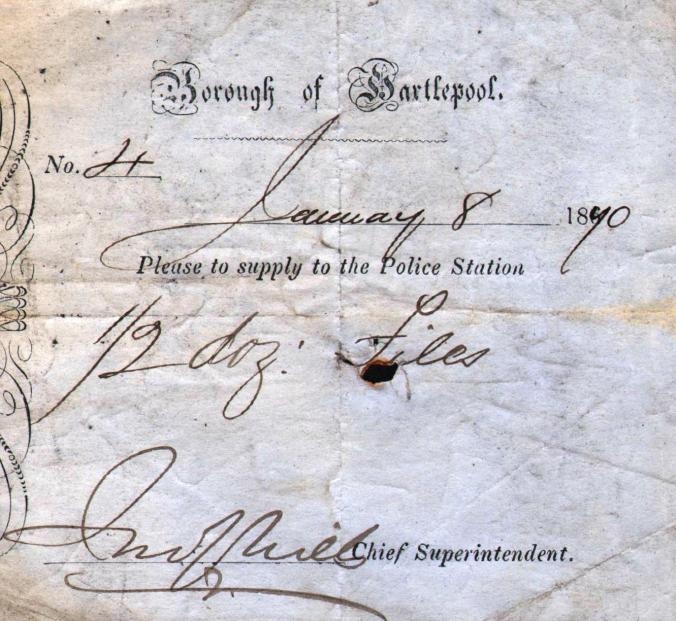

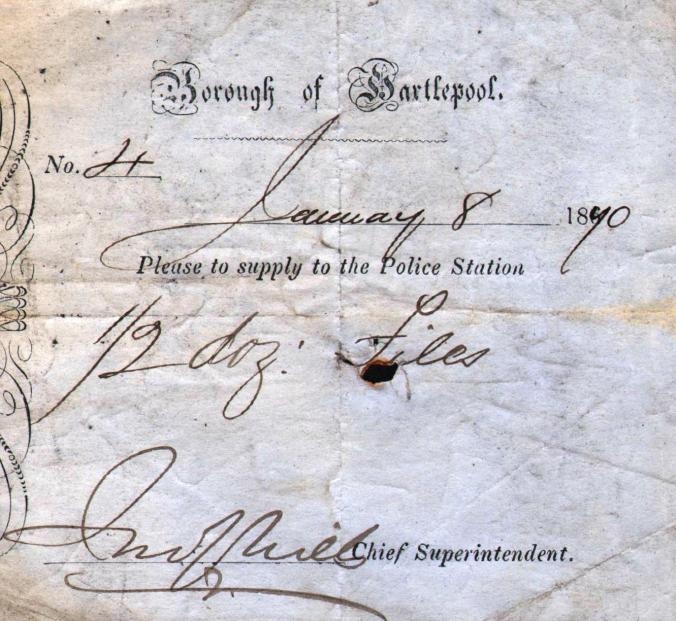

By January 8th 1870 John Shiels was in position as ‘Chief Superintendent’ at Hartlepool Borough Police and ordered 1/2 dozen files. Here is a sample of his signature.

In July 1866 John moved his family to Scarborough after he was appointed Inspector of Detectives. John remained at Scarborough for two years before moving to York City Police as Detective Inspector. John was thought of highly at Scarborough and on his resignation was presented with a gold watch; “as an especial mark of our cordial regard and high appreciation of the manifold services you have rendered to the town of Scarborough, while acting as detective in the Police Force of this Borough.” (Extract taken from Assembly rooms, Testimonials, Scarborough, 8th February 1868, J.W. Sharpin, J. P., Scarborough).

After moving to York John’s third and fourth children, John and David, were born in quick succession in 1869. That same year John was named one of four Detectives involved with the apprehension of three criminals convicted of felony in the Norfolk area. The other detectives were from Birmingham, London and Norwich. Together, with a Superintendant from King’s Lynn they received £10 as a recognition for their skill and activity in the capture of the criminals.

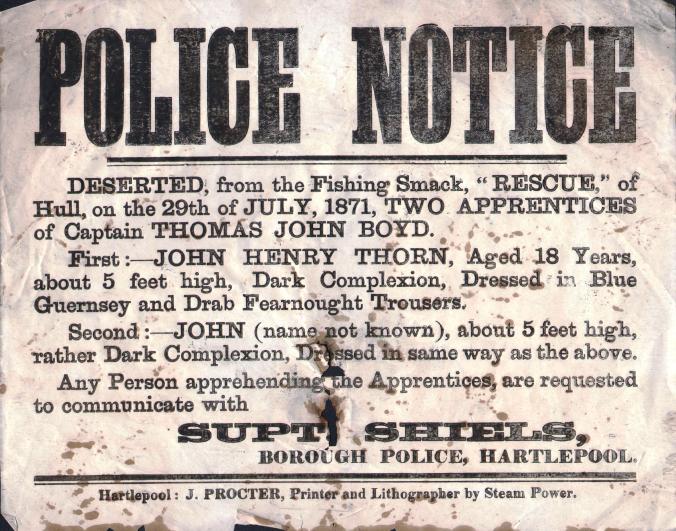

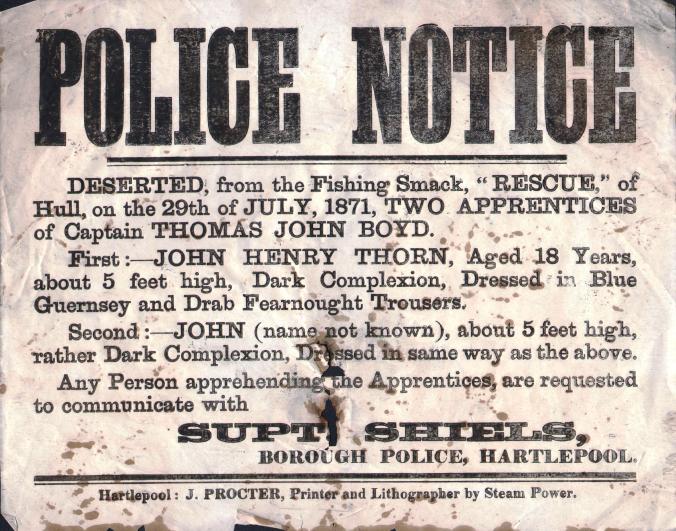

Police Notice from Superintendent John Shiels of the Hartlepool Borough Police, regarding two men who deserted from the fishing smack “Rescue” of Hull in July 1871.

In January 1870 John Shiels was appointed Chief Constable of Hartlepool Borough Police. At the time the Hartlepool’s were made up of two towns; Hartlepool Headland and West Hartlepool. In 1851 the Headland re-established its ancient Charter of Incorporation and thus pulled away from the Durham County Police Force (which policed West Hartlepool) and established the Hartlepool Borough Police – overseen by the Watch Committee of that Borough. When John took over as Chief Constable the force had only been in existence for 19 years, and he was the second Chief Constable.

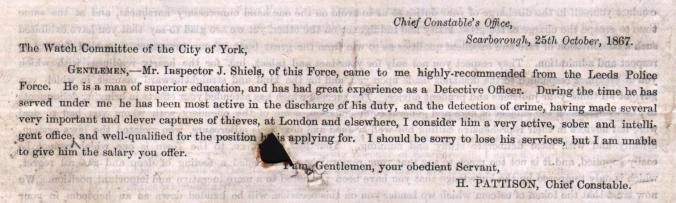

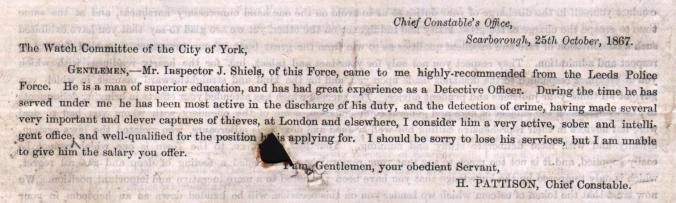

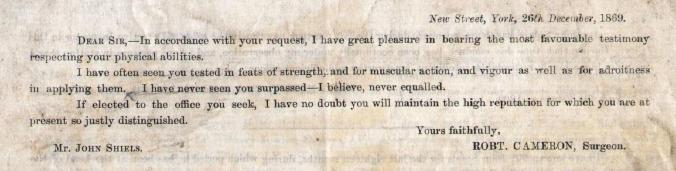

The job included a house, gas and coals, which amounted to approximately £15 plus £120 per annum. This was a huge step up for John, whose testimonial for this position still survives as part of the Robert Wood Collection at the Museum of Hartlepool. Here are a number of quotes which are testament to John’s character at the time of his appointment.

Reference given by Chief Constable H.Pattison of Scarborough Borough Police, to the watch committee of the City of York, 1867

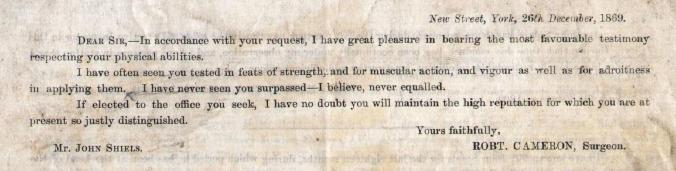

Reference given by Surgeon Robert Cameron of York, 1869

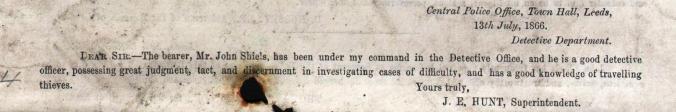

Reference given by J. E. Hunt of Leeds City Police Detective Department, 1866

Only a year after moving to Hartlepool two of John’s children died, David aged 2 and Margaret aged 7. John and Selina had three surviving children; Patrick, John and new born Mary Agnes. In 1873 another child, Helen was born, and in 1875 another girl, Kate, followed.

In 1874 John’s salary was reported to have increased from £130 per annum to £150 per annum (York Herald 10.1.1874) implying that the Hartlepool Borough Council Watch Committee were pleased with John’s work. Only a year later however John resigned his position as Chief Constable after a period of only five years. We have no information regarding the reason for John’s resignation or the demise that was to follow.

In 1877, two years after John resigned, he and his family were living near Leeds where another child, Emma was born. Two years later in 1879, Charles was born and a further two years later in 1881, the tenth and last child, Christiana Virginia was born. John was registered as a ‘Hawker’ which would have been something of a reduction in salary and quality of life – so why did John do this? One theory is that something happened to John in 1875 which meant that he was forced to resign his position as Chief Constable (perhaps he turned to alcohol after the death of his children? – sobriety was an important characteristic for a Chief Constable). He turned to the only other occupation he knew, ‘hawking’. He may have found this difficult to do in Hartlepool as John would have required a licence from the Chief Constable.

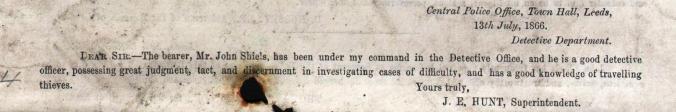

Police Notice from Head Constable John Shiels of the Hartlepool Borough Police regarding the burglary of the Mayor of Hartlepool’s house, 1873

Selina died aged 42 in 1881 and was buried in a nonconformist site in Leeds. Three years later in 1884 John, married his second wife Margaret McIver (nee Goldie). Margaret had previously been married to a West Yorkshire police officer who had died in service, because of this she received a payment of £70 as compensation. Together they had ten children all under the age of twelve – six of which belonged to John. Their address at the time was 9 Meanwood Terrace, Leeds. Again, John’s occupation was described as a ‘commercial traveller’.

Margaret died three years later and it would appear that this was something of a turning point for John who was starting to find life difficult, as we can see by the following displays of behaviour:

- On 24th October 1887 John was charged with assaulting his nine year old son in their home. John, “when sober behaved well to his children”. (The Leeds Mercury Tuesday 25th October 1887) As stated by various newspaper reports at the time, John received a sentence of two months hard labour. Three of John’s younger children were put into institutions.

- In 1888 there was court case against John, this time for ‘annoying passengers on the railway,’ According to the Yorkshire Post Thursday 12th April, John is described as a Book Hawker, of Newcastle, ‘When the train had passed through Marsh Lane Tunnel he commenced dancing about the compartment and annoying the lady, and making himself objectionable.’ Although he didn’t appear in court he was ordered to pay a fine of 40s (shillings) plus costs or one month in prison.

In 1906 John is recorded as having died – although there is limited information as to the circumstances of this.

One of the interesting questions we are left with is what happened to John Shiels while he was living and working in Hartlepool as Chief Constable? Why did he leave a well paid, prestigious job, where he was well respected in the town to become a Hawker in Leeds? was it the pressure of losing children, or did he simply wish to live a more simple life? We may never know the answers to these questions and so we might be left to fill in the blanks with only the facts we have. Please feel free to discuss what you think may have happened to John Shiels in the comments.

Images copyright to the Museum of Hartlepool, Robert Wood Collection.

With particular thanks to Janet Richardson and family whose research into John McAdam Shiels (2nd Great Grandfather) has formed much of this research.